FPUSA:

You draw from such deep recesses of life experience to make your work. It’s inspiring to see how open you are and the power that comes from that.

Shraya:

Throughout my career, I’ve seldom thought, explicitly, that I’m going to pull from personal experience. For me, the process of making art has been about doing so. Art and personal experience, for me, go hand in hand.

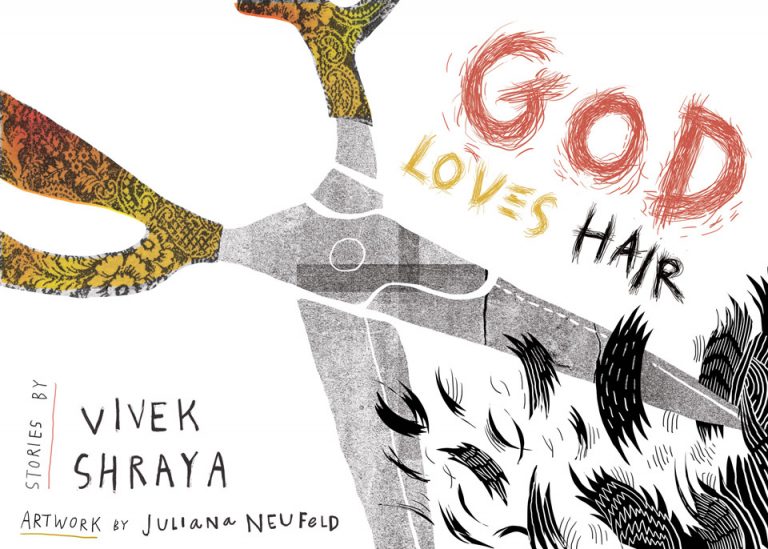

However, I will say that it was the lack of success with my music career that I had in my 20s that opened me up to writing. I was starting to feel like music was never going to happen for me, but I still needed to feel creative so I started to write what was to become my first book, God Loves Hair. The personal narratives that I explored in music tended to circle around love and longing, and I think moving away from songwriting momentarily was actually quite freeing. Suddenly there was so much I wanted to say about what it meant to be queer and gender nonconforming, and having immigrant parents, and growing up in an immigrant household. Those are all things that I, at the time, didn’t know how to express in music and had been given the impression that music could not hold. So I will say that my music career not taking off was what pushed me to pull deeper from personal experience.

FPUSA:

And then you made a great return to music!

Shraya:

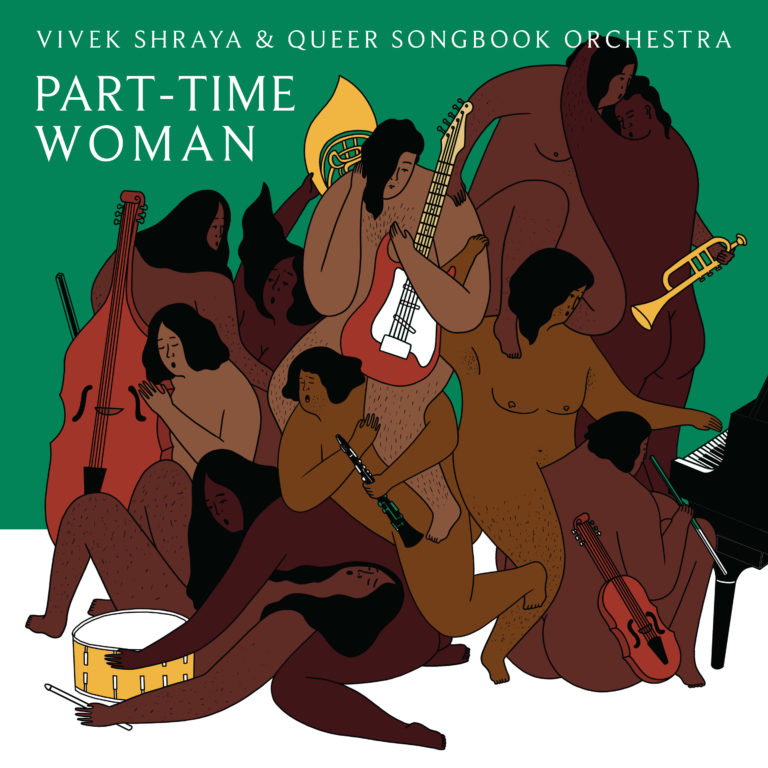

Last year, I put out my first solo album in six years called Part-Time Woman, which was recorded with Queer Songbook Orchestra, and it was the experiences that I had in writing and in making film over that six year span that really inspired that album. Suddenly I felt like all the things I couldn’t sing about in my 20s, or that I was encouraged not to sing about in my 20s, I knew how sing about and wanted to. So Part-Time Woman explores gender, and misogyny, and lateral violence, and a lot of themes that I had only felt I could explore in more traditional forms of writing. In that six year span I ended up forming a band with my brother as well, called Too Attached. We put out an album this year, Angry, which is a reclamation of racialized rage and is really about people of color owning our anger.

FPUSA:

How did this sibling collaboration come about?

Shraya:

Our relationship in our late teens and most of our 20s was really fraught, and it was through music that we started to reconnect. I ended up singing on an album of his, and he ended up beatboxing on an album of mine and then scoring a film of mine. So in our late 20s, early 30s, we started informally collaborating with each other.

It was really interesting to just circle back to music because, as much as my brother and I have a lot of differences, we did grow up in the same house. We have a lot of similar references and influences. My dad’s entire Bollywood collection and 80s pop collection were all part of the music that we listened to. So it felt really seamless in a way, for us to grow into a more formal collaboration, which we call Too Attached.

It’s definitely a work in progress. My sibling relationship is probably my most challenging relationship. Sometimes I feel like forming a band with my brother is maybe the most challenging thing I’ve ever embarked upon as an artist. But we just have so much respect for each other, and when I’m on stage with him I kind of go back to that childhood place to sitting next to him at our religious organization and singing. There’s something about it that feels so comforting and nostalgic and familiar and fun. I’m really proud of Shamik and I’m excited about what will happen next for us.

FPUSA:

Your practice is full of collaborations beyond this collaboration you have with your brother. What role does collaboration play in your creative process?

Shraya:

I’d say the first half of my art career was solely music, solely making albums, and for the most part was quite solitary. It’s interesting because that’s also the most invisible part of my career, and there’s something about that time that feels lonely. Important, because I do think I was developing a voice and a sound, but also lonely.

Then in writing my first book, God Loves Hair, I ended up collaborating with an illustrator, Juliana Neufeld, and the process truly felt collaborative in that we wrote and illustrated simultaneously. She would send drafts of her illustrations, and the better her drafts got, the more I wanted the writing to be better. So I would add details to my writing, and her next illustrations would include some of those details. It in some ways felt like building a friendship through art, which I’ve really grown fond of doing.

I’ll never forget when I met Juliana for the first time to talk about my artistic vision for the project and brought her, in true Vivek fashion, a stack of 50 visual references, a lot of them from Hindu iconography. My general idea for illustrations for the book was a modernization and a queerifying, I guess, of Hindu iconography. For instance, Hindu iconography will feature Krishna eating from a spilled bucket of butter. My idea would be, ‘How about we draw Krishna, but he’s applying lipstick instead,’ or something.

I remember Juliana coming back and being like, ‘I like this idea, but ultimately what you’ve written is so much more contemporary. I worry that if we just borrow or try to reinvent existing iconography that it will be a disservice to your story.’ And for me, this has been the beauty of collaboration. As an artist, when you are working on your own projects, you have no sense of objectivity. It’s all tender, it’s all personal. But there’s something about working with other people, especially people who are invested in the project and want the project to be the best that it can be, that allows for a certain different perspective to emerge, for the art to become more nuanced and perhaps even broaden its ability to connect with others.

So in some ways, perhaps it’s not surprising that my increase of success and connection have been tied to collaboration, as opposed to my solo work. I’m sure that’s not the only factor, but I’m curious about it being a factor, because that’s certainly a significant shift between the first half of my career and the second half. So moving forward, I have no desire to make a solo album ever again. I already know what it’s like for me to write a song on my own. I’m really curious about what happens when artists come together.

Vivek Shraya is an artist whose body of work crosses the boundaries of music, literature, visual art, and film. Her 2017 album with Queer Songbook Orchestra, Part‑Time Woman, was included in CBC’s Best Canadian Albums of 2017, and her first book of poetry, even this page is white, won a 2017 Publisher Triangle Award; her next book, I’m Afraid of Men, will be out in Fall 2018 from Penguin Canada. She is one half of the music duoToo Attached and the founder of the publishing imprint VS. Books.

A Polaris Music Prize nominee and four-time Lambda Literary Award finalist, Vivek was a 2016 Pride Toronto Grand Marshal, and has received honours from The Writers’ Trust of Canada and CBC’s Canada Reads. She is currently a director on the board of the Tegan and Sara Foundation and an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Calgary.

No comments yet.