“Maybe I will define family by what I believe it’s not. I don’t think that family is conditional to being related by blood. I don’t think family needs to be centered around romance or sex, I don’t think family needs to center children or monogamy. It’s not really what family is, but that’s off the top of my head what family isn’t.”

– Vivek Shraya

Tracing Vivek Shraya’s timeline of creative expression is an exhilarating exercise that speaks to the immense depth and interconnectivity of her work. In fact, the more you look into Shraya’s creative practice, the more you suspect her obsession with connective tissue – not just between the various disciplines she engages in: songs expanding into books, poetry grounding performance, music production deriving from filmmaking – or in the way she examines and re-examines the interrelation of race, gender, joy, anger, and identity. Shraya’s work is also rich with connections among people – her many collaborators and real, imagined, and internal audience, and her care towards these connections make them feel as fun as they are life-sustaining.

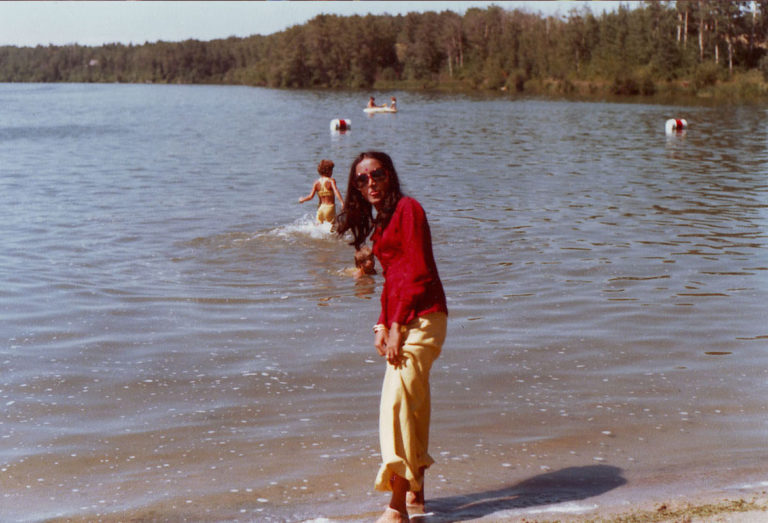

For her exhibition Trisha, curated by John Chaich at Ace Hotel New York, Shraya created what she calls a photo essay, in which she recreated newly encountered photographs of her mother from the ‘70s and wrote an artist statement in the form of a letter. The exhibition is an exploration of many things, including motherhood, a generational change, and the artist’s transgender identity, but at its core, it’s a tribute to Trisha.

In anticipation of the closing reception of Trisha on August 27th, coinciding with the launch of her tour celebrating the release of her new book, I’m Afraid of Men, we had a chance to chat with Shraya about her creative process and the collaborations that fuel her.

Family Pictures USA:

Your mother’s photos are part of an archive that you first came across three years ago. Can you tell me about this archive and what it was like to come across these photos?

Vivek Shraya:

As someone who’s active on social media, I understand that photos are snapshots of a moment but can also be curated

My immigrant parents have been through what they call a slow project of “downsizing” in their old age. They took all of our old childhood photo albums and paid very little money to get it all scanned. The photos themselves don’t exist anymore. One day my brother and I receive six disks, and they’re like, “Here you go, here’s our family photos!” All on disks. Aside from being like, “What happened to the photos?” I was curious about just going through them.

I grew up with a very organized mother – something that I also probably inherited from her – so our photo albums were sectioned by human. There’s my brother’s photo album, and my photo album, and then the general family album – photos we’re all in. And then there’s this mysterious disk of photos I’d never seen, and it turned out to be photos of my parents’ wedding and their honeymoon when they first arrived in Canada.

As I mention in the essay, I was really surprised by how happy and in love my parents look because that wasn’t the relationship that I witnessed as a child. I had all kinds of emotions. I think one of the strongest ones was guilt – that assumption that children ruin their parents’ lives. It felt like I had evidence of this, and it made me sad to think of the ways motherhood may have stripped my mom of her joy that I saw in photographs.

Of course, as someone who’s active on social media I understand that photos are snapshots of a moment but can also be curated. In one of the photos in Trisha, my mom is holding a stuffed animal, and I can’t imagine she did that willingly. I’m sure my dad coerced her into doing that. So objectively I know that what I see isn’t the full picture, but that was my initial response to finding those photos.

FPUSA:

I loved that photo pairing, by the way, of you then holding the elmo.

Shraya:

One of the biggest decisions that had to be made when embarking upon this project was how precise the replicas had to be. I worried that if it became a project that was obsessed with 100% perfect replication, any small difference would then take away from the project. So I decided with the photographer, Michelle, that it was more about recreating the energy and the feeling as opposed to re-creating absolutely every element in the original photos. Adding certain differences felt like an interesting way to inject humor, and Elmo was definitely an opportunity to inject humor. Elmo also represents a different time than the time in which the photos of my mom were taken, which was likely to be the late ‘70s. Other decisions included having the laptop with a clock screensaver on it as opposed to a formal clock, or being on a cell phone as opposed to using a corded phone. Those were all opportunities to just mark time and the difference of time.

FPUSA:

Once you re-created the set, was there anything unexpected that came out of the performative nature of the project?

Shraya:

One of the most surprising and at times challenging parts of the project, both during and after, was realizing that my mom and I were actually quite different. This was a project that was envisioned around a form of similarity, but even when I was putting on a sari it felt very foreign to me and very uncomfortable. Even though so much of my gender presentation has been influenced by my mom, I definitely felt like I was wearing a costume while taking these photos. It was surprising because on some level I thought that I would be walking in more familiar shoes, but instead it felt like I was somebody else and trying to understand who that person was.

For example, the first photo of the series is my mother looking up at a framed photo from her wedding with her arms are crossed, as a newlywed. As someone who was trying to recreate my mother, it did feel surprising to then stand there, have my arms crossed, look up at that photo that I grew up seeing all the time, and wonder what might actually have been going on in her mind.

FPUSA:

Thank you so much for sharing that. That’s such a complicated feeling – trying to introspect into our parents’ lives, especially as the children of immigrants. In your essay, it’s a revelation to find out that the title of the show, Trisha, is what your mother would have named her daughter. How did you come to understand that name or persona?

Shraya:

While I’ve described the project as a tribute to my mother, it’s also a tribute to the daughter that she wasn’t allowed to have. The project, to me, is a tribute to Trisha. So I wrote about how my mom prayed to have two boys because she didn’t want to have a girl, and yet, simultaneously, we grew up knowing that had my mom had a girl she had a name picked out, and that was Trisha.

What I love about calling the project Trisha too is the assumption that it’s my mom’s name. For me it’s very much a photo essay, not just a photo project. It’s very much about the relationship between the photos and text, and if you don’t read the essay, you might assume my mom’s name is Trisha. But for me, it felt more important to name it after the daughter that she prayed not to have, and the viewer doesn’t know this connection to the title until the last line of the essay.

No comments yet.