By Evan Trine

I’ve been working on this body of work for the last year or so. It developed slowly after stripping down previous bodies of work until I realized that the source imagery I’d been using was actually the most interesting, valuable part of my process. I haven’t completely landed on the language around this work – it’s hard to take an intuitive feeling and put it down into words! I stole this phrase from my friend Ry Rocklen when talking about some of his recent work, but it’s just spot on: “This new work is dedicated to the forms of the hyper familiar, and investigation of human subjectivity through the archetypal objects of our existence. It aims to reclaim and exalt the serialized object.”

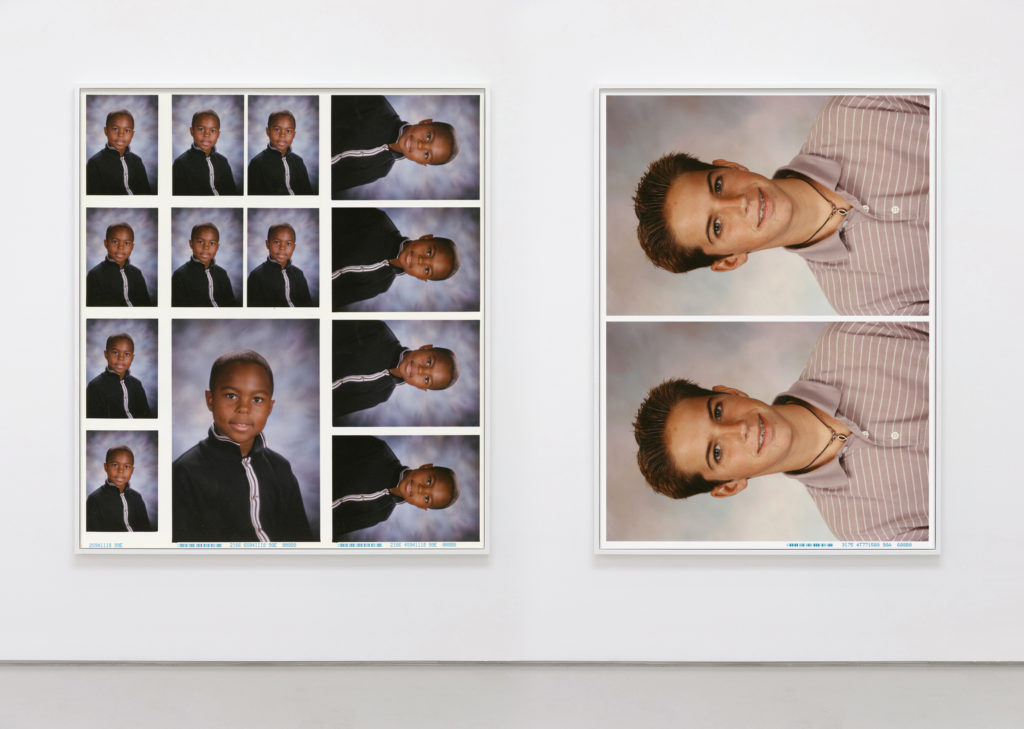

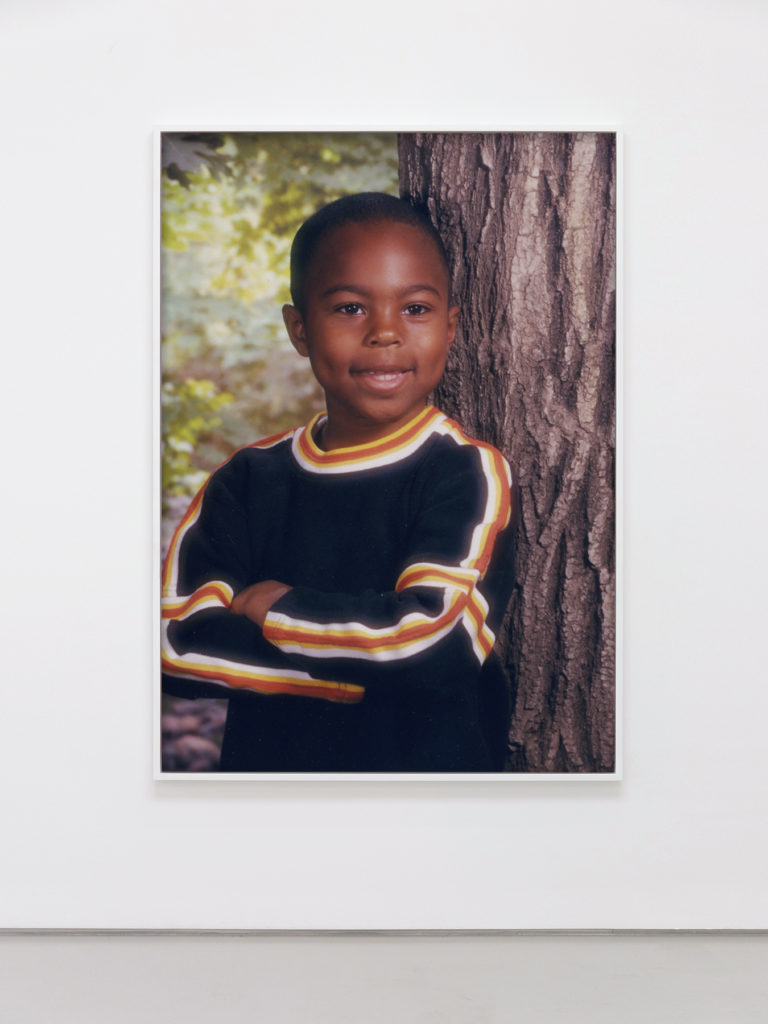

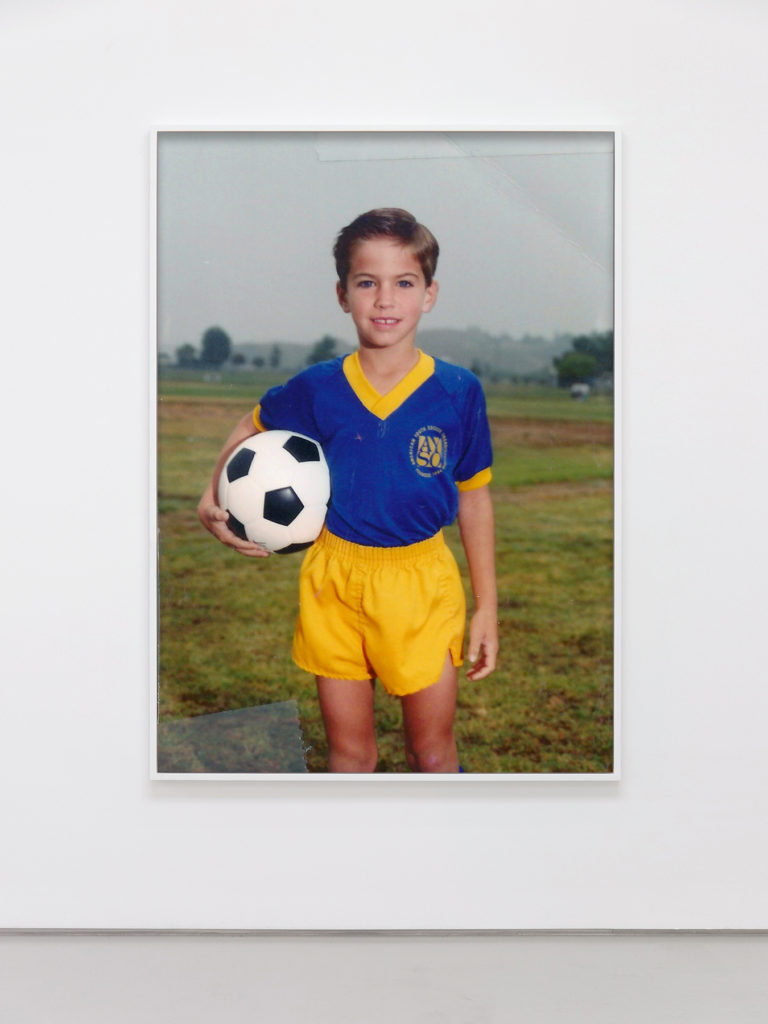

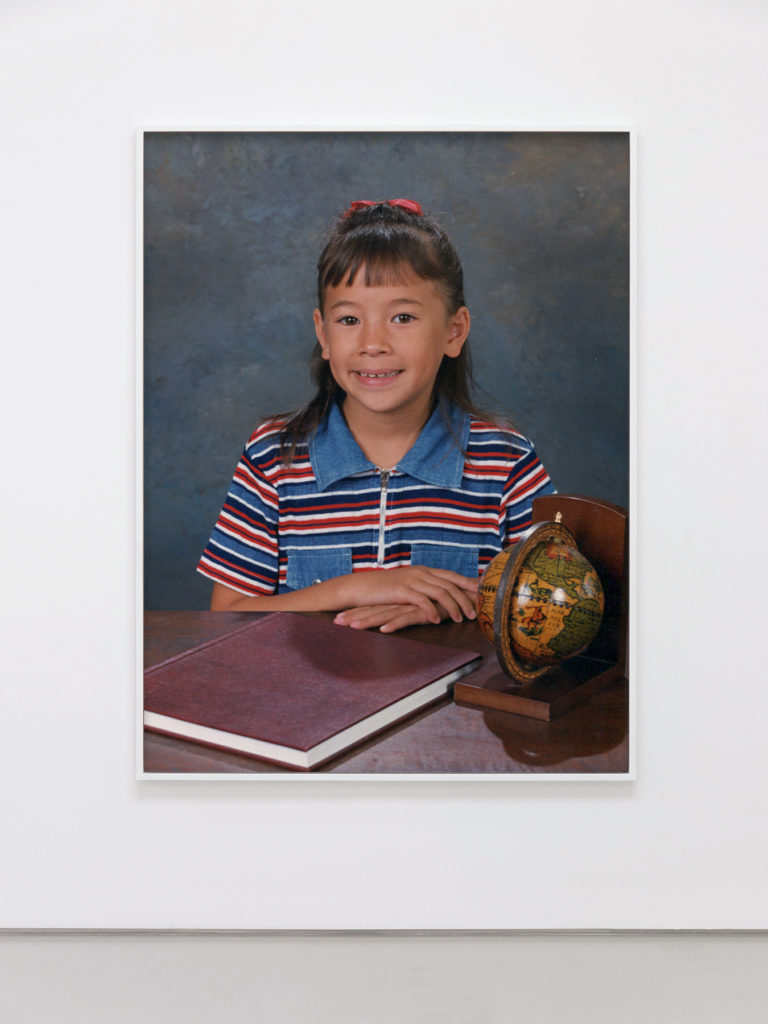

For this body of work, which I’m tentatively calling my “photo day” series, I’ve taken old family photos from my family and friends – mostly school portraits, sports portraits, and the classic studio shots from the mall that we used to get in the 80’s and 90’s. I was originally using these images as source material for a more abstract body of work, but I couldn’t deny the allure of the original, unedited scans. So I decided to print one out really large, hang it in my studio, and live with it for a while to see what thoughts would develop for me.

I quickly realized that these photos had a lot to give me as work in their own right, not just as content for creating other work. I started to gather more and more photos of my family and friends – I’ve looked through literally thousands over the past year trying to find the photos that have a certain hard-to-define quality.

Eventually, after dozens of studio visits and a lot of research and discussion, I was able to determine a few things about this work, and why I was so drawn to these photos:

“Photo Day” is one of the most democratic, almost egalitarian experiences. Everyone I’ve spoken to, from all different generations, states, and countries has participated in photo day – either at school, or with youth sports, or for family holiday photos.

Regardless of wealth, race, gender, location, education – we have all participated in this system. We get photographed in front of the same backgrounds, with the same props, by the same company (often times). It’s truly a universal experience, which I think is really rare, and interesting to note on it’s own.

These images were from the last era when physical photos had this type of value. These are the last photos from the pre-digital camera/cell phone/social media age. These photos were our identity. Your fall school portrait was often the only proper photo you got that entire year. I have one photo that represents “Evan, age 8”. This is why I love the creases, tears, scuffs, dust, and tape residue still visible in the scans. These are printed very large (6 feet tall), so all of those details are very visible and play a role in the work.

This is a ritual. We collect these photos year after year, in every size; so we can have one in our wallet, on our desk at work, on the mantle, in the photo album, give one to grandma and grandpa, aunt and uncle, all our friends, etc. We share them with everyone to showcase our participation in this ritual, and at a larger scale, our participation in society.

This photo isn’t just a cute picture of my brother playing soccer, this tells everyone, “We are doing it! Organized sports! He’s athletic! He’s masculine!” These photos represent a set of social and cultural ideals, and these photos are how these ideals were perpetuated.

The source images that work the best feel like stand-ins for an archetype: “cute daughter”, “sports boy”, “successful child”, “adventurous son”, “happy couple”, “loving family”. They feel almost like stock photos. I’m not interested in the specific story of this child – I’m interested in the image of them that represents a larger imbedded idea.

In the context of the gallery space, these mundane, everyday photos are revealed to be encoded with strict social and cultural ideas like race, gender, religion. Enlarging them and putting them in a room together brings out these loaded concepts, and they can’t be ignored. Seeing a 5×7 of your co-workers son on their desk doesn’t necessarily conjure ideas of masculinity, sexuality, whiteness… but in a space that is made for critical discourse, among other images embedded with other loaded concepts, these ideas are brought to the forefront. This doesn’t have much value on it’s own, until you realize that we ALL have participated in this. We all have these photos that represent much more than what is shown.

These are a handful of my disjointed ramblings – I’m currently working with the directors of my gallery in Los Angeles, Roberts Projects, to finalize this work and the language around it.

What I loved about Family Pictures USA was hearing and discovering all of the narratives behind our family photos, and how they connect so many people. Where I think my work differs is that I’m not focused on the unique stories of the individuals in the photos – rather, how we are all connected through this process of serially photographing and documenting our lives. And obviously our work is similar because I’m dealing with very similar content. But beyond that, we are both acknowledging a valuable connection through the fact that we all have similar photos of us, our families, our kids, our parents – we all share this experience and these memories.

Evan Trine is a photographer and fine artist living and working in Long Beach, CA. He received his MFA from Claremont Graduate University and is currently represented by Roberts Projects in Los Angeles. He has exhibited extensively in the Los Angeles area, and at art fairs nationally and internationally.

No comments yet.