By Eric K. Washington

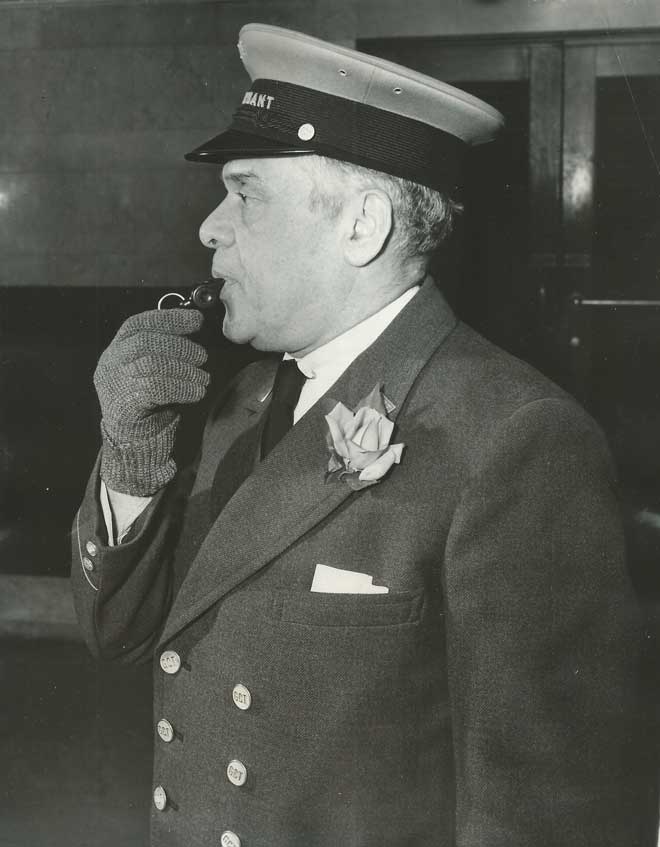

“At the Grand Central station is a colored man who probably knows more people than any other Negro in New York,” a front page lede in the New York Age read in 1923. “He is Chief James H. Williams, head of the Red Caps of the Grand Central station.”

James H. Williams’ forgotten story is important and overdue for a biography. It deserves deeper exploration as a profoundly insightful window on Harlem, and the “harlemania,” of storied times. Williams was as aware of the intellectual voices of the “New Negro Movement” that were crucial to black progress as he was of the white “slumming expeditions” that thrilled to the singing and dancing nightspots that were in vogue. He had a keen vantage point of the proverbial passing parade, maintaining a sure footing in the antipodes of downtown Grand Central Terminal and uptown Harlem. He had direct agency in the nascent developments and unfolding histories of each, and to each demonstrated a lifelong loyalty. My biography aims to chronicle this fascinating New Yorker’s life as he sheds the legacy of 19th-century enslavement, navigating through his city’s uneven intersections of race, ethnicity and class to realize his own 20th-century middle-class achievement. Williams’ story is still both poignant and timely. While James H. Williams’ story is obviously one about race and labor, it is overwhelmingly also one about personal industry, resourcefulness and philanthropy.

Williams’ narrative reveals the qualities that ultimately positioned him and his legion of “Red Cap” workers as iconic cultural touchstones of both the Grand Central Terminal and of the Harlem community. The trajectory of his life—which begins and closes in the wake of the Civil War and WWII, respectively—ever navigates the kaleidoscopic social and political landscape, and reveals Williams’ remarkable complexity. He was at once a management functionary and a community hero. In the former capacity, as a New York Central Railroad assignee—whose 45-year tenure encompassed two world wars, the Harlem Renaissance & Great Black Migration and the Great Depression— Williams ushered statesmen, movie stars, society elite, sports heroes, high clergy and other notables to and from trains with marginal visibility. Yet in the latter capacity, James H. Williams was part of the central nervous system of the Harlem Renaissance. African Americans deferred to him as “the Chief”—the “czar of the grips”—who created a platform to employ black men and to showcase the entire race in the most admirable light.

James and Lucy Williams with son Pierre in August 1916 while at Lipscomb Cottage, a black resort in Atlantic City. Charles Ford Williams Family Archives

Heavyweight boxer Joe Louis, right, arrives by train in New York on July 5, 1936. Between the champion’s shoulder and the edge of the frame is James H. Williams, Chief and the Grand Central Terminal Red Caps. ACME Press Photo

Eric K. Washington is an independent historian and the author of the book, Manhattanville: Old Heart of West Harlem. His proposed biography of James H. Williams (1878-1948), the former chief porter or “Red Cap” at Grand Central Terminal, received the City University of New York Graduate Center’s Leon Levy Center for Biography Fellowship 2015-2016. He is a recipient of the Municipal Art Society’s (MAS) 2010 MASterworks Award for his permanent interpretive signage in West Harlem Piers Park. Eric is also currently a fellow in Columbia University’s Community Scholars Program 2014-2017, awarded to enable continued research contributing to his various writings, talks and tours that shed light on Upper Manhattan’s rich local history, which include his biographical subject Chief Williams.

Thomas Allen Harris interviewed with Eric K. Washington. Below is the text.

Thomas Allen Harris (T) : Could you describe this project on James H Williams, Chief of the Redcaps. How did it find you or you find it. What was the genesis of the story?

Eric K. Washington (E) : My introduction to Chief Williams began with Grand Central Terminal’s 100th anniversary in February 2013. I was doing research in preparation to give walking tours of the station for the Municipal Art Society and decided I’d also write something about it for the occasion. I knew there was a long history of African Americans working for the railroads. I really wanted to know something more about the people who worked there. I knew that A. Philip Randolph had played an important role in organizing the Sleeping Car Porters, or so-called “Pullman” porters, and at first I probably thought they and Red Cap porters were interchangeable names for the same job. I quickly learned how distinct their jobs were—the former road the rails, the latter worked in the stations—but also quickly understood kinship of their jobs: both were service occupations, both were almost exclusively identified with black men, and both were formidable contributors to the establishment of the black middle class. As I started researching, Red Caps kept coming up in old news stories about the new Grand Central Terminal because they were crucial to the Swiss-watch precision of the terminal and woven into the heady, glamorous experience of early 20th-century railroad travel. Many of their names also came up in the chronicles of the social, cultural, athletic and business enterprises that coincided with the captivating growth of America’s most famous black community: Harlem. That’s where James H. Williams came in, a “race” man. Described as the “czar of the grips,” Williams was officially the Chief Attendant of Grand Central Terminal, in which capacity he enabled hundreds of young black men to pay their way through university by toting baggage as railroad station Red Caps. But there was the other Chief Williams who was also the liaison to most of the celebrities who passed through the great terminal.

T : What role did the photographs play in your discovery of Williams story. Could you speak about the types of images that you found of him, what you learned through reading them and what impressed you about them?

E : The first image I ever saw of Williams was in a 1910 article about him in Harlem’s New York Age newspaper. Unfortunately, the gritty cameo was the most legible facial closeup I had for a time. Two years later, I got a scan of the original photo from his great-grandson’s family collection and I was beside myself. It was crisp and clear, and I could make out the form of an antler-headed lapel pin. The tiny ornament pointed towards Williams’ active membership in fraternal orders. I already knew he was an officer and convention delegate in Harlem’s Manhattan Lodge No. 45, one of the largest bodies of “colored Elks.” Even better, a crumbling corner of its surrounding mat board still revealed enough of the name and address of Otto Sarony, 1177 Broadway, one of New York City’s most noted photographic studios, near West 28th Street. This photo is significant to me because it holds up a visual reference of the young James H. Williams in early 20th-century New York. Here he is, appropriately dapper in one of the city’s most fashionable hotel and shopping districts, whose streets stretch westerly into those passing African American homes, meeting rooms, and businesses in one of the city’s so-called “black belt” enclaves. In the 1880s and 1890s, these were the streets he’d grown up on, where he went to school, where his father worked, where he came of age and took jobs has a hotel bellman and a flower messenger. It is where he began the process of marriage, family-making, and community building. And although that elegant photograph was taken downtown, it also makes reference to the community-building that Williams contributed to some five miles farther uptown. That little lapel pin locates him in Harlem.

T : At a certain point in biographies, it seems like a law of attraction comes into play and fact, information and images seem to emerge and present themselves. At least I’ve found that working on documentary-based film and art projects. How you found most of these images of Williams?

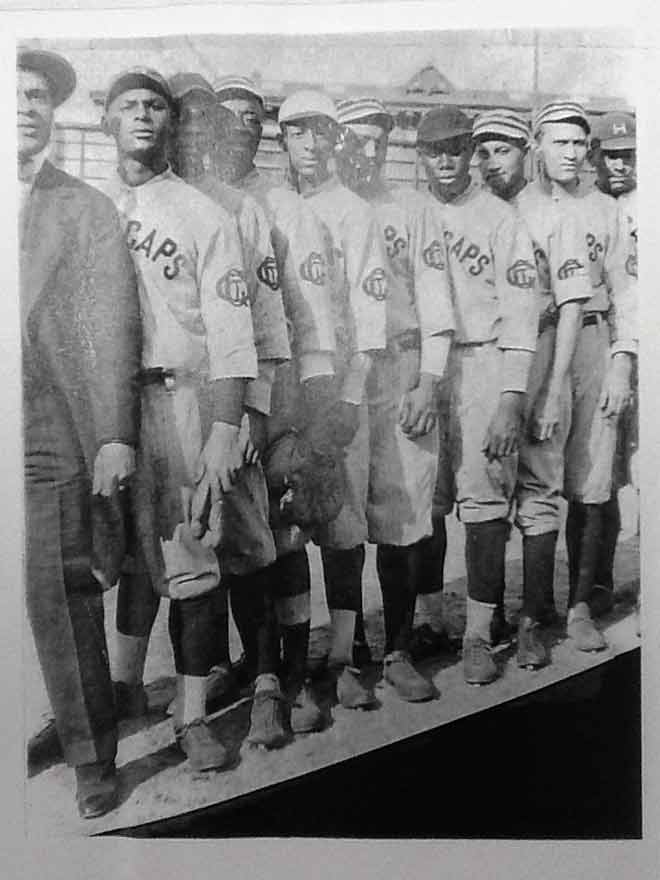

E : Some by direct solicitation from gracious Williams family descendants, like his great-grandson Charles Ford Williams, who authored a book about his grandfather Wesley A. Williams, who was New York City’s first black fire official and the son of James H. Williams. Others I’ve found in various collections and news archives, such as the personal papers of Howard “Stretch” Johnson, Jr.—the son of a Red Cap baseball star, Howard “Monk” Johnson—in Columbia University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library. Or online archives of the New York Central Lines Magazine. Finding publication-quality photographs from defunct or unarchived newspapers is a constant challenge, but locating press photos has paid off on eBay a few times, too.

T : I’m thinking of the image with Joe Louis where Williams resides at the edge of the frame as an elderly man yet in many ways he was just as significant as this celebrity. Why is this image important to you? What does it say to you?

E : A journalist once remarked: “No Grand Central passenger can consider himself a big shot until Jim has personally met him.” For me, this photo conveys the considerable power that statement implies. I imagine thousands of railroad travelers passing through Grand Central Terminal daily, measuring their respective arrivals and departures by their anticipated encounters with Chief Williams. True, he inhabits the edge of the frame, but with the poise of an honor guard. I suspect that’s why the photographer made him part of the picture. In this photo, where Williams is keeping apace with Louis, who was also a friend as it were, I can imagine his keen vantage point of the world as it paraded through the Terminal. Like Joe Louis, Chief Williams enjoyed his own celebrity uptown, albeit of a more modest kind. In Harlem, African Americans constituted the population most keenly affected by the city’s jim-crow racial practices, and were aware of the distinct color line delineating Grand Central station’s workforce. It was not lost on the “race” that Williams’ ability to put as many as 500 black men to work at a time was nothing short of heroic. A newspaper commented in the early 1920s that Williams “probably knows more people than any other Negro in New York.” To be sure, he had direct agency in the nascent and coinciding histories of both downtown Grand Central Terminal and uptown Harlem, and demonstrated a lifelong loyalty to both as well.

T : What were some of the most surprising images you’ve come across of them? And what can we learn from their visual story? (What visual moments are you aware of that celebrate these men – either statues or within popular culture or would this book be the first?)

E : A good number of photographs are occupational shots whose matter-of-fact 20th-century Jim Crowism is unfortunately too familiar. Every man is conspicuously African American, engaged in the nature of a Red Cap’s work that the writer E.B. White once observed, “tends to put him in a class with beasts of burden.” You see them wending their way through of the Grand Central’s opulent, bustling concourses, staircases and platforms while heaving trunks and satchels. They’re also often tucked with spoiled pets or children, balancing golf clubs and hat boxes, opening taxi doors or rolling out running carpets. Piled with the photographs, the numerous and varied illustrated ephemera and stereotypical “negrobilia” figurines of Red Caps have ranged from the subliminally derogatory to the grotesquely descriptive. To me, such images thrust forward a very powerful counterbalance in the self-generated images of Red Caps themselves: the gritty pride of the Red Cap baseball players, showing off their team colors; the Red Cap Orchestra, assembled to perform; and especially James H. “Chief” Williams himself, whether poised to join a delegation of the Elks, to promenade the boardwalk at Atlantic City or to greet the Twentieth Century Limited, in from Chicago. These latter images compare closest with those that populated the walls and dressers of my own and other- African American families.

Do you have an interesting story or research subject to share? Family Pictures USA is always happy to showcase new and heretofore unknown stories and images that help us all to better understand our history. Share your story!

No comments yet.