Photographs curated by Daniela Spector

In 1976 my mom, Norma Spector, went to Vietnam as a member of an international women’s delegation at the invitation of the Vietnam Women’s Union, representing Women for Racial and Economic Equality (WREE), an organization she helped found and lead. The Vietnam War had ended but the devastation had not — millions dead and wounded, vast swaths of the country made uninhabitable by unexploded ordnance, napalm, and chemical defoliants, babies deformed by in utero mutations. She was amazed that she was treated with such kindness, with such honor, after what her government had done to her hosts. She met a woman who had lost her son in the war. The woman cried as she recalled losing her child. What grief is more profound and less consolable? Mom, crying, leaned over, put her arms around the woman, and said, “You can have my son.”

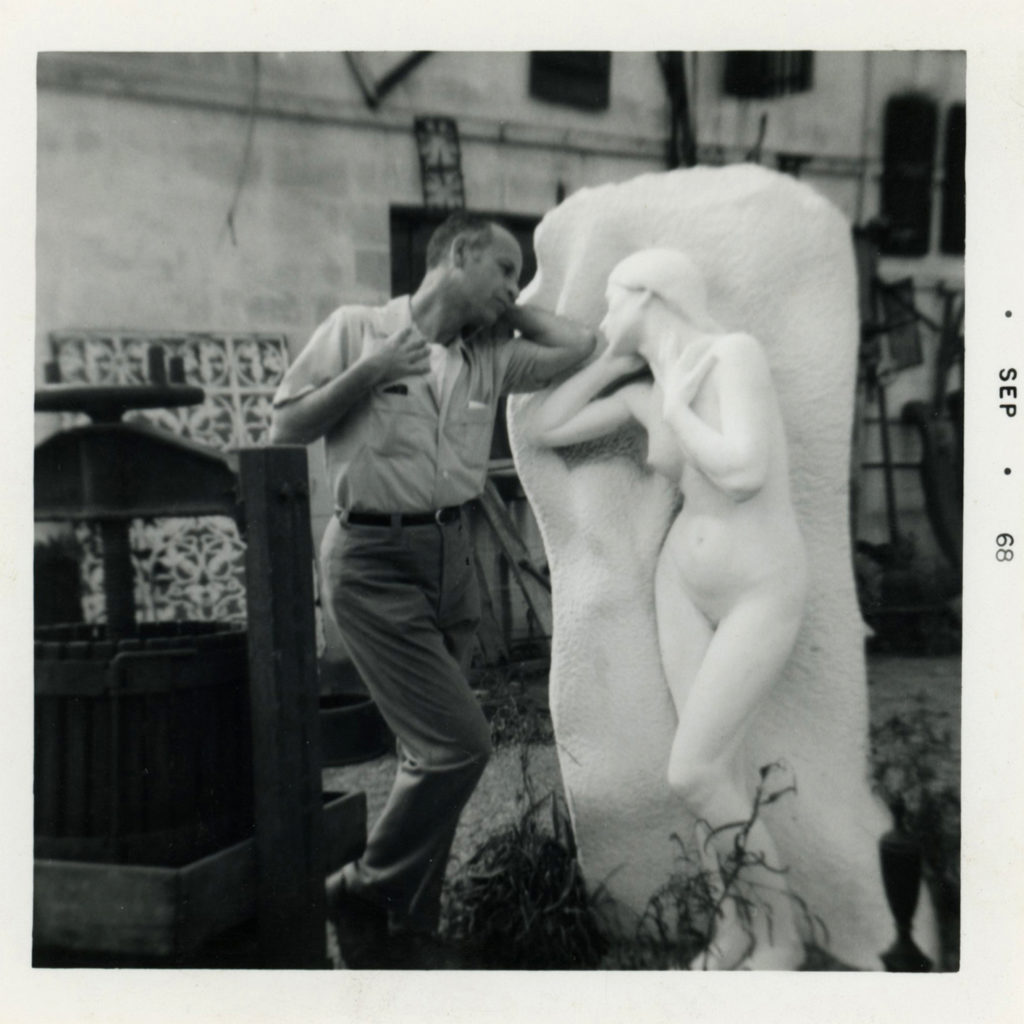

My dad, Harry Spector, had a wonderful sense of humor. When Mom told him that a book she had read was a classic, he responded, “How can it be a classic? I haven’t read it.” During a road trip in 1968, Mom and Dad stopped at a store with statuary out front; Mom took photos of Dad posing with one of the statues.

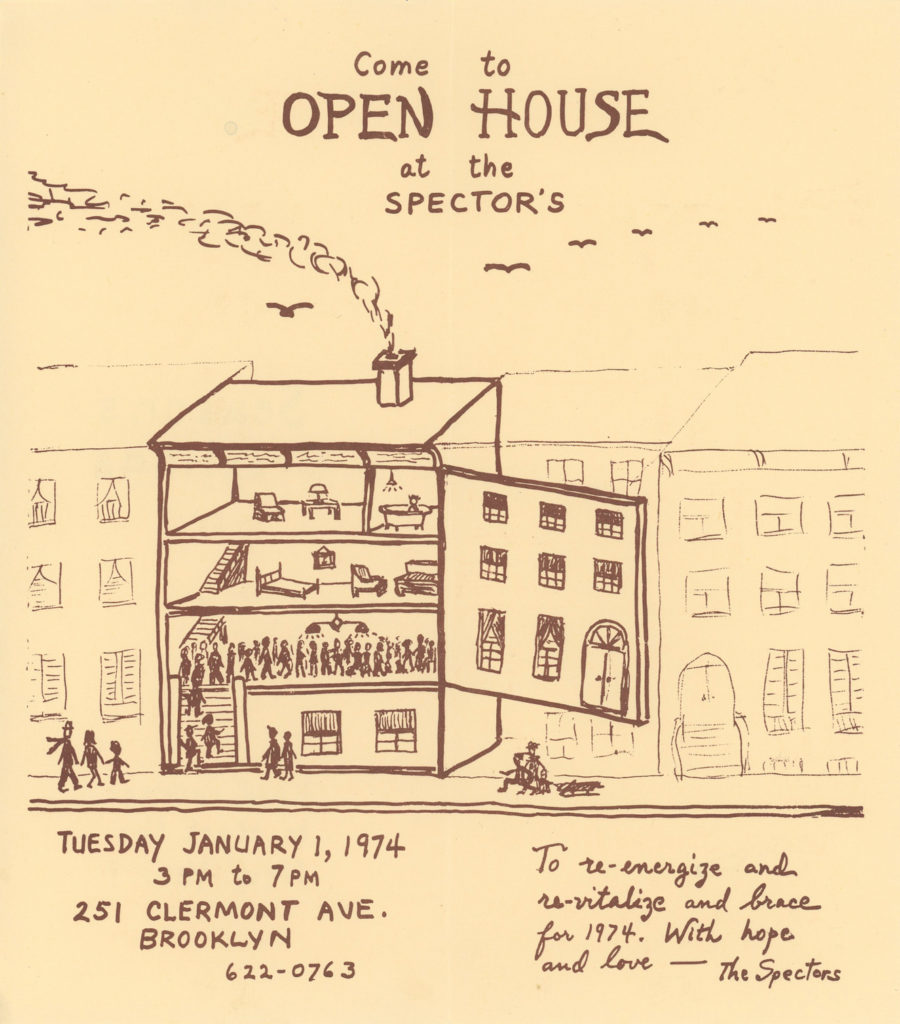

He drew cartoons and made funny faces. He designed the invitations for our open houses on New Year’s Day, which drew dozens of people.

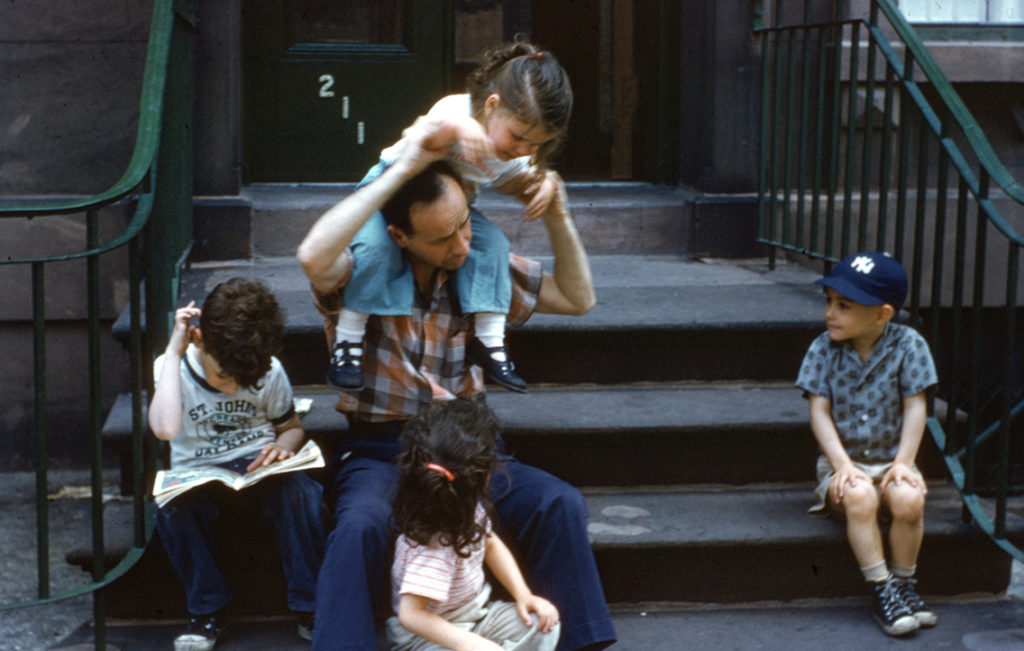

Dad was by Mom’s side in the social movements she was a part of, from Women Strike for Peace and Brooklyn Congress of Racial Equality in the 1960s through WREE from the 1970s to the early 1990s. Mom and Dad would sit at the dining table and fold leaflets and address, stamp, and stuff envelopes. He helped her edit the WREE-view for Women, WREE’s magazine. Mom never worried about the home front — Dad was there. He was as involved in the home as she was. If she had an evening meeting, Dad made dinner for my sisters (Debby and Rachel) and me, including my favorite: bananas and sour cream.

Mom and Dad’s political work didn’t start when they married in 1952. Mom was active in the solidarity movement in the late 1930s with the people of Spain defending the country in a civil war against Spanish fascists backed by Hitler and Mussolini. After World War II she joined the movement to bring attention to the human rights violations against and incarceration of Greek Communists and others by the CIA-backed Greek government. Dad was a union leader at the Aberdeen, Maryland Proving Grounds, where artillery for the U.S. Army was tested. In the late 1940s he and four other Jewish union leaders were dismissed because of “national security.” He was then fired from a job as a Baltimore high school math teacher during the McCarthy era witch hunt.

Mom’s and Dad’s parents were among some 3 million Ashkenazi Jews who immigrated from Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1924. Dad’s parents, Sarah and Samuel Spector, who immigrated in the late 1880s or 1990s, met on a homestead in Denver, Colorado.

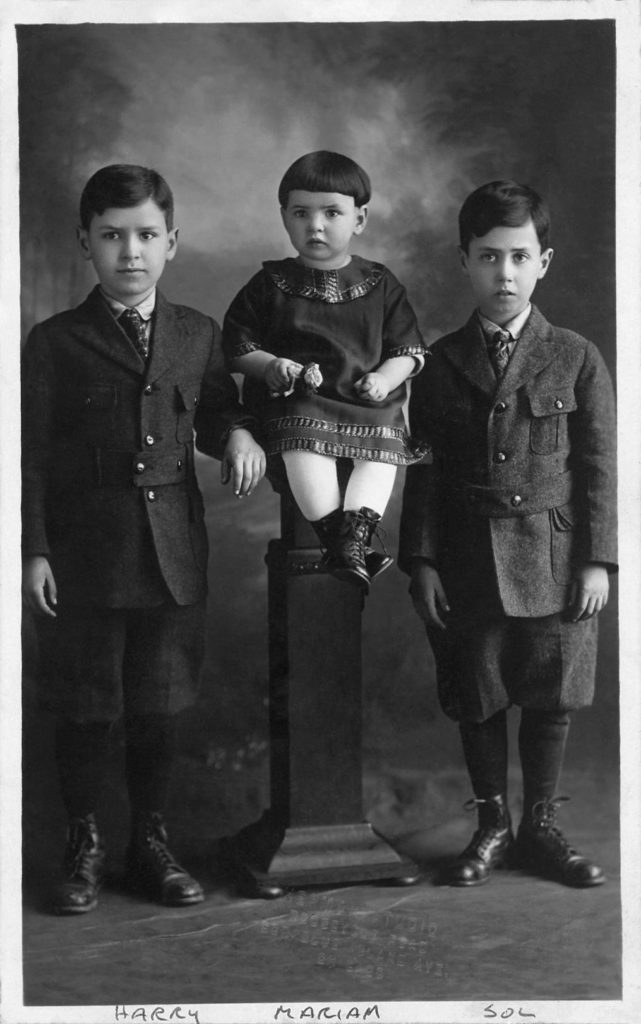

Dad was born in Denver in 1914. The homestead didn’t work out, so the family moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where my Uncle Irving was born in 1915. A few years later, baby Joseph was born but died during the 1918 flu pandemic. The family moved to Chicago, where my Aunt Mariam was born in 1921. My grandparents had a tailor shop and Aunt Mary recalled Al Capone’s goons coming in and threatening violence if the family didn’t pay protection.

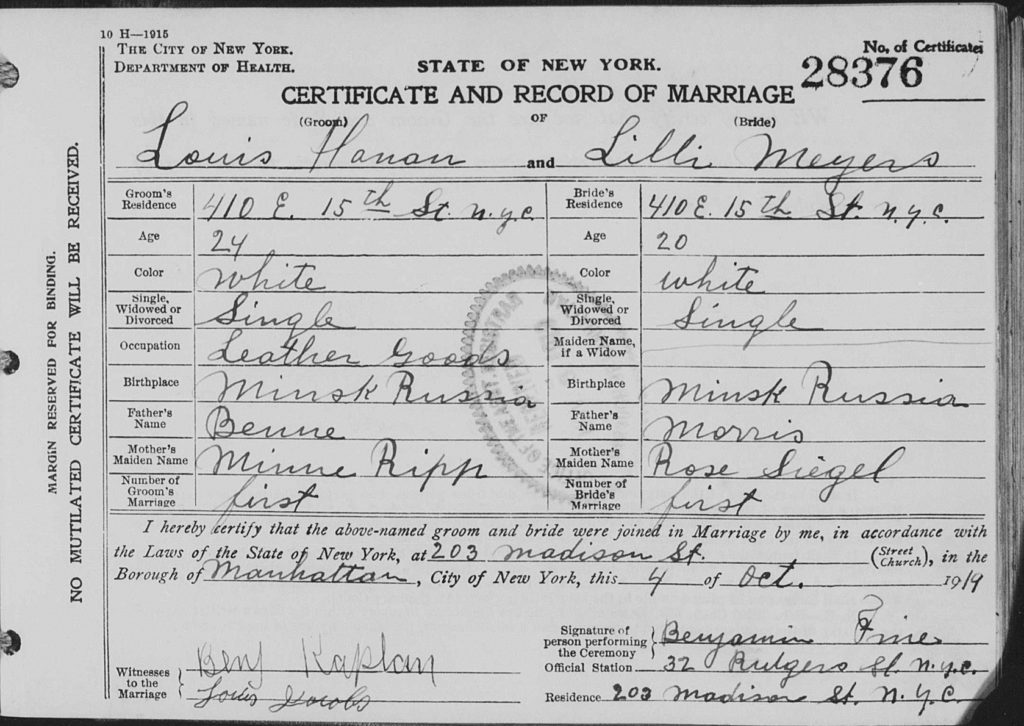

Mom’s mother, Lilli Meyers, came to this country with her older brother, Albert. She was probably around 12 years old. They never saw their parents again. Her 1919 marriage certificate states that she and Louis Hanan were both 20 years old and were from Minsk, which was then part of Russia.

Mom was born in 1922. Her brother, Robert, was older. We assume he was born shortly after Grandma and Louis were married. Louis abandoned the family when Mom was around 6 years old. Grandma went to work as a garment worker, but it was not enough to make ends meet. Mom recalled the three of them begging in Times Square, and having to move every couple of months when Grandma couldn’t pay the rent. Robert abandoned them when he graduated high school.

Mom left home when she turned 18, after years of physical and emotional abuse. She remembers her mother yelling at her as she walked down the stairs, “I hope your bus crashes and you die!” After the war, Grandma married Morty Still, who was “Papa” to my sisters and me. Mom decided to marry Dad when he brought her to his family’s seder in New Jersey and she saw family members laughing and hugging and just enjoying being together. She and Grandma reconciled — sort of — when we grandchildren were born, but she continued to address her mother as “Mother.”

In 1965 we (Mom, Dad, my sisters Rachel and Debby, and I) moved from a seven-room railroad flat on the top floor of a four-story walk-up on St. James Place in Bedford-Stuyvesant, to a four-story brownstone on Clermont Avenue in Fort Greene. Both communities are in Brooklyn, New York. Aunt Mary joined us. Mom and Dad created out of that 19th-century building a home that was known among many people in the movement as the Spector’s. Hundreds of people passed through our home over the next three decades. Relatives, friends, comrades. People who needed sanctuary for a day or for a while. People who sought advice, counsel, or a shoulder to cry on. People who came to meet, to marry, to learn, and to raise money. Someone remarked at an event, “It’s like the UN in here.” And Mom fed them all. Food was just another form of love.

(I wrote about the home that Mom and Dad created, in a short story entitled “The Parable of the Wooden Table,” which I published in my Thoughts-letter on Substack. You can read the story here.)

In the early 1990s the mishpocha (“extended family” in Yiddish) moved to Miami. Mom and Dad were retired, but not from being Mom and Dad. By then, they were Grandma and Grandpa to five children and, after 2000, great-grandparents to six more children.

When his health began to fail, Dad wrote a letter to Mom:

I love you and the kids and their loved ones and Mariam and my best to all our wonderful friends. I am sorry for the hard times I caused you and I know you reciprocate, but overriding all that — we had a wonderful relationship, witness the wonderful children we have. I am glad our lives intertwined; much of the meaning in my life derived from the values and important work in your life. I hope you will carry on, bravely and constructively, as always.

Dad died on the Sunday before Thanksgiving Day in 1996 after a months-long struggle with prostate cancer. He was 82.

“During Grandma’s last few days,” my younger daughter Daniela wrote to me, “some of the cousins and I were listening to stories of her life. We asked her how she could do all her work with three kids. ‘I had Harry,’ she said with a quiet smile.”

Mom died in 2013, four months shy of her 91st birthday. She left us these haikus, of which she wrote, “I am inordinately — and probably undeservedly — proud”:

I grew tired and stopped

Before I could change the world.

But that’s vanity!

Don’t grieve, I’m content.

If you love one another,

I was not in vain.

Danny thank you for sharing such beautiful family memories and photos of dear Norma and Harry, and the whole Spector klan. Norma is remembered with much love.

Thanks, Sania. I hope you are well.