When I presented my DDFR workshop at “Beyond Borders: Diverse Voices of the American South” in February, I was moved by everyone’s level of engagement and care in their fellow participants. One particular person, Hanul Bahm, spoke emotionally, clearly connecting with everyone’s stories at her table. I asked her to gather some recollections about her table, which was actually one of the largest of the conference:

“Entering the giant auditorium at UNC-TV in Durham on Feb 20, I was a mix of feelings and nerves. The Center for Asian American Media (CAAM), based in San Francisco, had organized a gathering of Asian American filmmakers living in the American South, a historic first. We were to spend a day together to talk about a demographic whose visibility, worth, and personhood still stand contested in this region. I didn’t know what to expect from the day. The South remains an uneasy identification for me.

After grabbing a plate of breakfast thoughtfully prepared by the UNC-TV staff, I scanned the auditorium for a table to sit at. I approached a near-empty table near the entrance and introduced myself to Sam. I asked if I could sit there. He said sure.

Six others joined us: Anita, Andrew, Naomi, Lana, Leah, and Clint. Other than Anita, who was assigned as my hotel roommate by CAAM and whom I met the night before, everyone else was a new face.

After Donald Young and Sapana Sakya of CAAM gave opening remarks, artist Thomas Allen Harris took the stage.

He told us about a portraiture project that had turned into a decade-long endeavor called Family Pictures USA. Thomas was traveling across the States, engaging families to share about their lives and memories through their family photo album. I knew Thomas was filming a television episode in Detroit. He had become the man in the white archival gloves, helping families locate their stories within the currents of history.

Thomas gave us a surprise exercise. He asked us to dig through our phones, locate a family photo and share about it with our tables. The energy in the auditorium shifted and crackled. I scrolled through my phone, wondering what was safe to share.

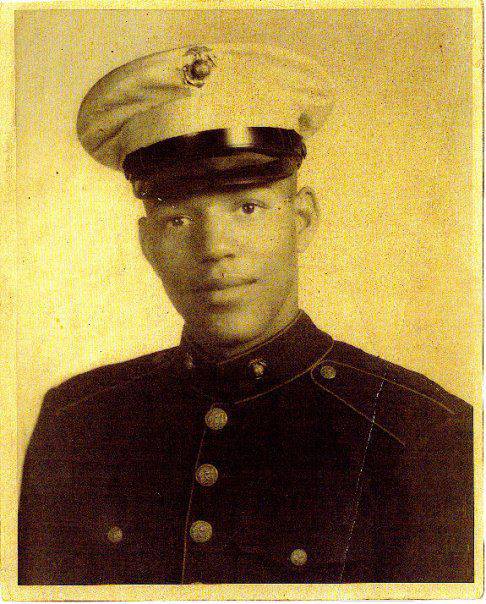

Lana Garland shared first. “This is my uncle Clarence, who passed away six weeks ago.” She showed us a studio portrait of a handsome young cadet in uniform. “People talk about having the crazy uncle in the attic or the basement. Clarence was that uncle for me. We loved him.” Lana had cast the first stone at our table. In so few words, she had disclosed so much and with dignity. As a Korean American whose homeland was the site of America’s “forgotten war,” I thought about the trauma we subject our veterans to, crippling and sometimes destroying them for the rest of their lives.

Naomi Walker shared next, showing us a black and white photo from a family gathering with kids. “I grew up in Richmond, Virginia, a very quirky town, with a big Jewish family who had moved down from New York,” Naomi shared. “This was my cousin’s Bar Mitzvah. My sister Ester showed up in fringes on her blouse, a cowboy outfit. She never wore a dress again her whole life.” Naomi is the one was standing on the table. Her cousin is in the center of the photo. Everyone else are Naomi’s sisters. Naomi was beaming. I thought of Ramona and Beezus Quimby from the Beverly Cleary books. And imagined a freed, non-gendered childhood for Naomi and her cousins.

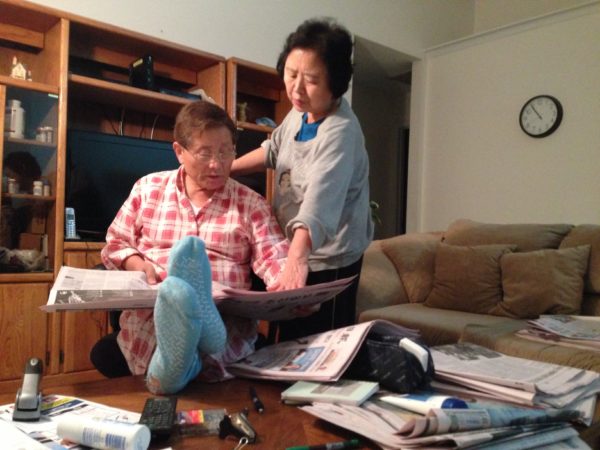

I was up next. “These are my parents who live in Lawrenceville, GA,” I said, showing a photo of my papa and mom, craning over his shoulder, reading the Korean language local paper. “They’re always consuming the news. Our living room’s been piled with newspapers since as far back as I can remember.” “The news has really infiltrated our lives,” I continued. “I say infiltrated because it’s all my dad talks about. It’s our dinner conversation. We never talk about ourselves, how our day was or anything else.” My voice was trembling—was I upset?? I was talking about displacement of psyche, something my family’s never really talked about. How had this become the norm for us?

Anita Sugimura was next. “This is my mom and me at Coronado Beach (near San Diego),” she began, showing a fun-filled selfie of herself and her mom. “My father had just passed away, so we visited this beach which held so many memories for us. Mom took her bento box and sat on the shore and had an amazing time. “It was the first time since the loss of my dad that my mom really laughed and found a measure of peace,” Anita continued. The night before, Anita had told me her father was a decorated U.S. Marine and had passed away in recent years. She had directed a documentary, Battlefield: Home, talking about the PTSD and the ripple effect and generational impact of trauma in the homes and family lives of warriors. It is currently doing the festival circuit. Anita had wanted to finish it before her father passed away, but he died during post-production and never saw the film.

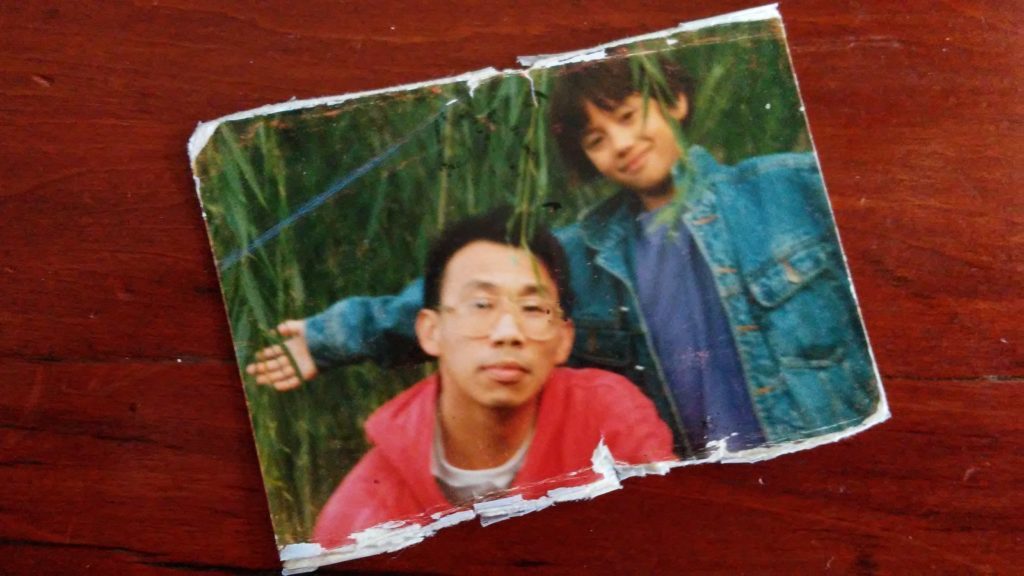

Andrew Young pulled out his wallet and showed us photo-paper photographs. “These are my children. They grew up with their mother in rural North Carolina. If you’re anywhere outside the major cities in the Carolinas, it was really hard being us.” The photo was of him and a child who looked like she was in grade school. “My kids are 32 and 30 now. My 30 year-old lives out in Berkeley, Calif, where she’s an activist. She has found support in the LGBTQ communities there. I’m very proud of her.”

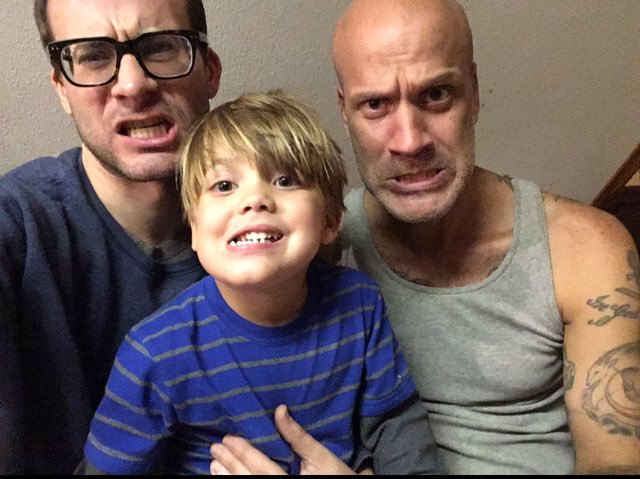

Clint Bowie pulled up a beautiful photo of him with another man and a young toddler boy, all smiles. “This is my family, my partner and our son.” He looked at Andrew and said, “If we go even 16 miles outside New Orleans, it doesn’t feel good. If we’re pulled over at a gas station, we get looks.”

Next was Leah Welsh. “This is me and my daughter,” Leah said. In the photo was Leah, peering into her car’s rear-view mirror at a seat-belted Asian American tween and a dog. “I always knew I wanted a rainbow family,” Leah said, explaining she had adopted her daughter. “I didn’t want her growing thinking she was different. We’ve talked about it. I want her to grow up happy. I think most days she feels that way.”

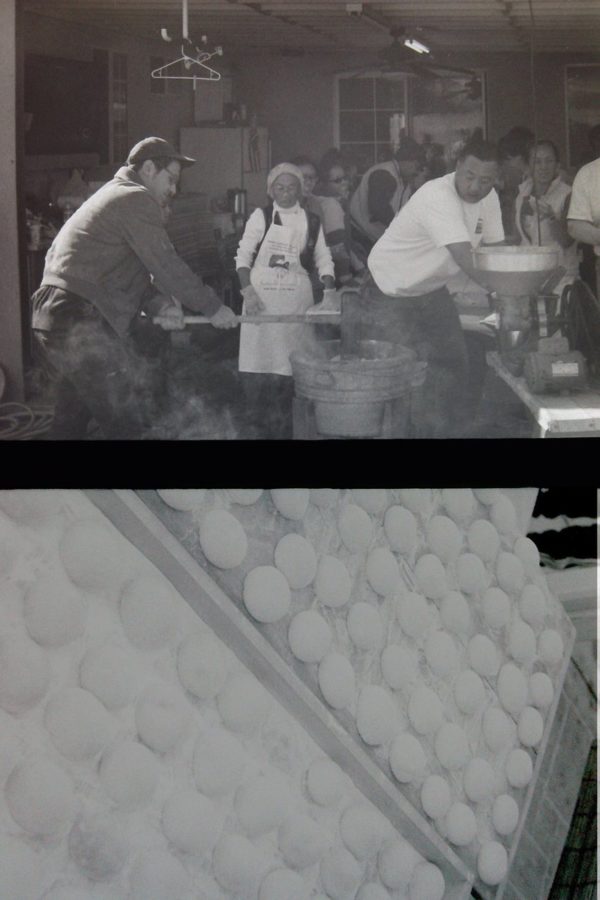

Last was Sam Parker, who shared a black and white photo of what looked like an assembly line kitchen. “This is us at Sakamoto Farm, my great-aunt and great-uncle’s family farm in the San Fernando Valley. We used to visit and spend time there.” I marveled that he had a photo of what looked like early Asian American history in his smartphone. “It was during mochitsuki, the mochi-making festival. I’m half Japanese,” Sam said.

And there it was, a current of sharing that traveled a circle and completed a circuit. There’s so little we can know about each other from surface appearances, even less from what we choose to share or not in polite company. Thomas’s prompt had given us the permission to be familiar.

In a time when photos have become social currency, it felt strangely good to relate to them as what they once were: keepsakes from our personal lives. I remain in gratitude of the level of disclosure our table summoned. And in a blessing no one expected or asked for, having to spend a day with a table full of strangers no longer felt like a burden. Our table had achieved a kind of trust and unity rare among acquaintances and colleagues.

I have people in my personal circle, people whom I deeply care about, who are emotionally unavailable. I don’t discount their humanity but it does make our dynamic hard at times. It might take them a year to disclose something as personal as what our table had just shared.

Thomas then asked each of us to go around and do a sharing out of what we learned about our table. Different tables took turns cheerfully summarizing common ground and themes that emerged at their table. No one seemed to want to step up to represent our table. We were all shifty eyes and like, “Um, you go.” I took the mic and with my table’s blessing, shared everyone’s photo story to the best of my ability. There was no way I could paraphrase what was shared.

Thomas later told me that my sharing was “granular,” that this exercise didn’t usually solicit that level of detail. All I could tell him was that it was important that it was shared this way.

No comments yet.