Family Pictures USA host, Thomas Allen Harris recently had the opportunity do a version of our roadshow for the United Philanthropy Forum. Robert Burnett, from the Maine Philanthropy Center, was one of the participants who joined him on stage. After the event, he agreed to write a short piece for our blog expanding on what he shared that day.

Robert with his sister Angel in Unity, Maine 2016.

Robert’s grandfather, Asador Ali.

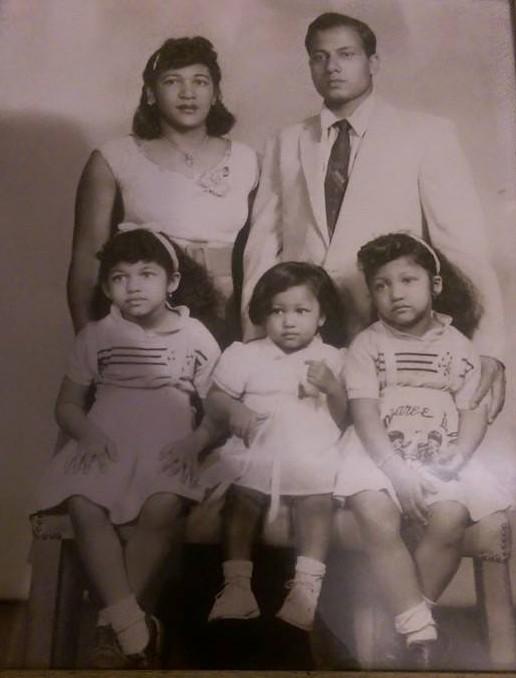

Lena (Mulluer) Ali and Asador Ali with their three daughters (pictured left to right): Hasina, Zainab, and Saida—Robert’s mom. Circa late 1950s.

I was born in 1983 to a Caucasian father from a small-town in Michigan and a Brown mother from New York City—their names, Robert Kris Burnett, Sr. and Saida Bibi Ali, as different from one another as their physical appearance and their cultural upbringing. The younger of their two children, I was preceded by my sister Angel. My parents divorced before I turned six, after which we lived with our mom in Maryland and visited our dad in Georgia periodically each year.

Unlike my sister Angel, her olive skin and dark brown hair striking a balance between our parents’ physical features, I am fair-skinned like my dad. She is frequently asked, “Where are you from?”, because her uncommon appearance makes many curious. Unless someone meets me in the context of my mother and sister, I am rarely asked such questions—people simply assume I am white, and act accordingly. Such tacit assumptions no doubt afford me many privileges associated with being white and male in the United States, and I have implicitly supported this systemic inequity time and again. Not because I value one of my heritages over another, but because for most of my life I’ve known so little about my mother’s background; and I’ve been intimidated by the task of claiming my invisible brownness. I saddled myself with the burden of proof and rarely mustered the courage to “prove” myself. In digging into my story, I just recently began to acknowledge the shame I’ve experienced for years about both knowing so little about what has powerfully shaped my identity and avoiding the topic with all but my close family and friends.

We grew up knowing almost nothing about my mom’s family. She spoke fondly of her father, Asador, recalling his culinary skill and a story of him jumping ship in New York City to start a better life in the U.S. She also doted on her mother Lena’s curly hair and “sing-song” accent. I never knew either of them personally and had only a vague idea of Asador’s visage from an old, damaged photo my mom treasured. My grandfather Asador passed away in the early 1980s, and my mother was estranged from her other living relatives. She was also reluctant to speak of her family, so I had little hope I’d ever know more about the lives of my grandparents.

Throughout my childhood, our closest family friends were most often Afro-Caribbean, African American, and Indian. I keenly identified with other 1st and 2nd--generation kids from immigrant parents and grandparents, and I always felt at home among diverse communities of color. Looking back on this pattern, it’s not surprising at all when in 2014, I along with several siblings and cousins connected via Facebook with a long-lost cousin who shared proudly with us our Bengali and Virgin Islander (St. Thomas) Afro-Caribbean heritage, including a precious photo of my grandparents and their three daughters. After thirty years, I saw their faces and heard their stories for the first time.

Since that revelation, I discovered that our family story is not entirely unique, but a thread in the tapestry of many other lost stories of Bengali immigrants who began families in communities of color in the late 19th and early 20th centuries1. The fullness of my rich heritage will never be made plain by my appearance, so I must use my voice to declare and affirm it. The opportunity to share this still-unfolding family history publicly with Family Pictures USA has begun a process of healing for me and ignited a new desire to not only know but also proudly tell my story.

Robert Burnett lives in Maine with his wife Rachael and is a musician and budding songwriter and craftsman. He studied both music and environmental science at the University of Maryland – College Park, where he deepened his appreciation for music from around the globe as well as the fascinating, resilient natural world we all inhabit. When he is not at the office as the Administrative and Research Manager at the Maine Philanthropy Center, he is typically working on renovating his old, Victorian-era home, making music, or exploring the wonderful Maine outdoors.

Thsnk you Robert for sharing your story