My Fort Myers Childhood Story

We are gearing up for our upcoming production of Family Pictures USA in Southwest Florida, where we will be exploring the families and community through their photographs and family albums for the second episode of the TV series. We are looking forward to uncovering hidden archives and personal connections to this diverse community along with WGCU, the Southwest Florida Historical Society, and the Florida Gulf Coast University Digital Archives, among others.

With two photo-sharing events in Fort Myers and Immokalee coming up this month, the Florida Weekly featured and interviewed our own executive producer Don Perry, who discusses the relevance of using the family photo album to find connections not only between family members but the people of the Southwest Florida community. Perry states that host Thomas Allen Harris is going to “build a storyline by connecting the dots between the different family narratives [they’ll] be gathering.”

One of our many family narratives for Southwest Florida comes from Cynthia Williams, who recounts her family history in Fort Myers. Cynthia’s grandmother, Elva Davis Williams, moved to Fort Myers during the post World War I real estate boom in the 1920s. With Elva’s three sons – Davis, and the twins, Bill and Berry – Elva found a job with an attorney and took on the challenge of moving as a single woman with three kids in tow.

Here is Cynthia Williams’s Southwest Florida story.

During the post WWI Florida real estate boom of the 1920s, the population of Fort Myers increased 6 times over. One of the hopeful new arrivals was my grandmother, Elva Davis Williams. She was 32 and single, with 3 sons to support. An adventurous younger brother had ventured to Florida and written home about the beauty of Fort Myers and the opportunity for gainful employment there, and with a challenging lift of her chin, Elva packed her bag, boarded a train, and went. She found a job with an attorney and when school let out back home in Fayetteville, Tennessee, her father put 14-year-old Davis and the 9-year-old twins, Bill and Berry, on a train for Florida. They rolled into the beautiful new Atlantic Coast Line railway station on Jackson Street in Fort Myers in June, 1925. Some 40 years later, Berry wrote about his childhood in a book titled, The Hickory Tree. The following excerpts from the chapter, ‘The Florida Fling,’ show us Fort Myers in 1925, as well as the killer hurricane of 1926, from the point of view of the ten-year-old boy who was my father:

“The Florida Fling” THE HICKORY TREE

In no time at all, Mother and we three boys were settled in a three-room, stucco house on Palm Beach Boulevard, at Van Buren Street. The house, set in the middle of a recently cleared palmetto patch, must have been a subdivision sales office. It was that small. The kitchen was a flat-rim sink with no drainboard, a two-burner oil stove, and an old ice box. We three boys slept in the largest of the three rooms, Davis and Bill on a double bed, I on an army cot with a quilt for a mattress. There was no running water except what dribbled from the rain water tank into the kitchen sink.

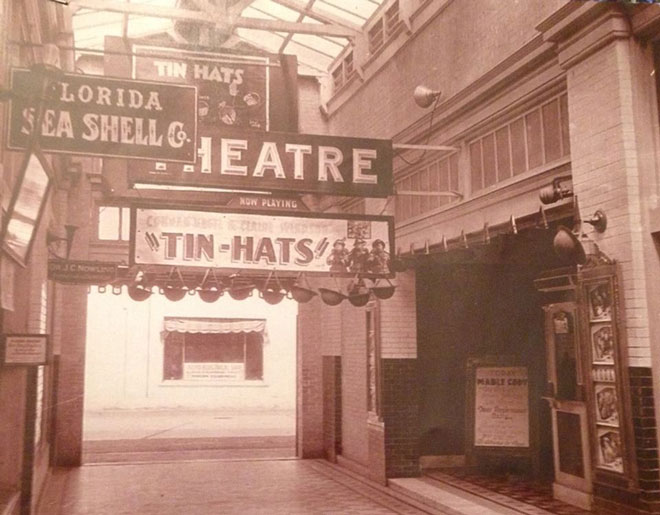

Palm Beach Boulevard had just been asphalted out as far as the newest subdivision, Russell Park. A half mile beyond Billy’s Creek was a new picture show called the East Fort Myers Theater. It was one of the two open-air theaters in Fort Myers, the other being downtown near the Lee County Bank. After Bill and I got a job selling newspapers, we saved enough money to go to the best picture show in town, the Arcade Theater. Shows there cost 15 cents.

About two months after we arrived in Fort Myers, Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush came to the Arcade. To advertise it, they were having a Charlie Chaplin look-alike contest. Mother and Edith got Bill and me all dressed up with charcoal mustaches and taught us how to shuffle and swagger like Chaplin. There was a big crowd the night of the contest, and we were frightened half to death…and greatly surprised when Bill won first place and I second. Bill’s prize was a month’s free passes to the Arcade, and mine a case of Nehi orange drinks. Bill’s prize was a windfall, for it meant that each of us saw every movie for a month. The pass was non-transferable, but the ticket taker didn’t know there were two of us. He thought it mighty queer that Bill saw each show twice, but Bill told him his mother said he could.

Often, when the shows were over and we had a long wait for the next Russell Park bus, we’d fortify ourselves with a cold glass of pineapple juice for a dime and walk the 2 ½ miles to our house. On the way, we marveled at the swanky Royal Palm Hotel on the river side of First Street. It was painted snowy white, and only millionaires stayed there. It cost $25 a day. A little farther out was the Elks Club and across the street from it was a beautiful two-story white frame house that had the prettiest yard I had ever seen. It was filled with palm trees, hibiscus, a Royal Poinciana and mango trees. Bill and I had never tasted coconuts or mangoes. We decided that since they had so many, they wouldn’t miss a few, so one day we sneaked into the yard and loaded our pockets with mangoes and our arms with big coconuts. We were halfway back to the sidewalk, when we were startled by a voice from the front porch. It was the lady of the house.

“Hello, boys.”

She asked us who we were and where we lived and then advised us not to pick mangoes from the trees, but to gather them from the ground because the fallen ones were riper and sweeter. We thought she was the nicest woman we ever met. But in two or three days, I was broken out all over with a terrible, weeping, running case of poison oak. Mother took me to Dr. W. H. Grace, a very fine doctor, and he told us that the mango was a member of the poison oak family and that the sap on the skin would poison one just as surely as poison oak. Dr. Grace gave Mother a pink liquid called Calamine lotion to dab on me. It did the job, but slowly. I was totally incapacitated and it was terribly hot. I lay for over a week on the army cot with the electric fan Mother borrowed turned on full blast.

When school started, Bill and I were enrolled in the third grade of the new Edgewood Grammar School. It was a beautiful, yellow brick building and our teacher was a very fine young woman named Miss Leola Leifeste. Thirty years later, when visiting Fort Myers after an absence of 29 years, I met Miss Leola at a parent-teacher meeting and asked her if she knew who I was. Without hesitation, she said, “Sure. You’re one of the little Williams twins I had in the third grade. I don’t know which. I never could tell you boys apart.”

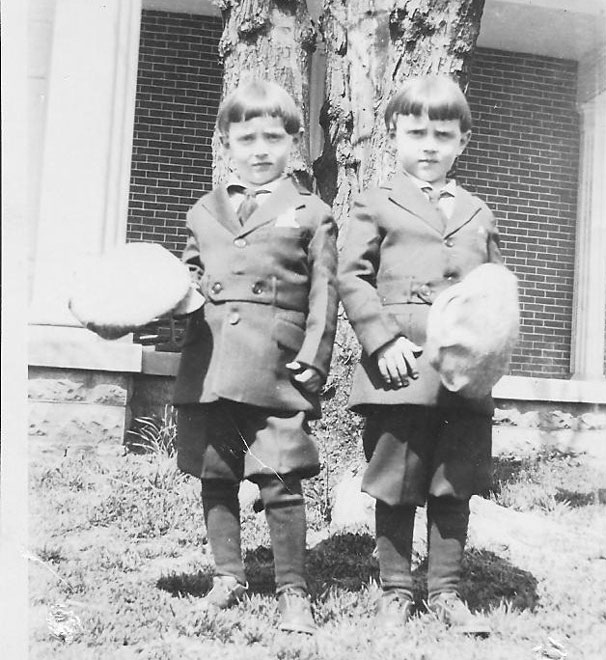

Berry and Bill, circa 1915, in front of their grandfather’s home in Tennessee. Photo courtesy of Cynthia Williams

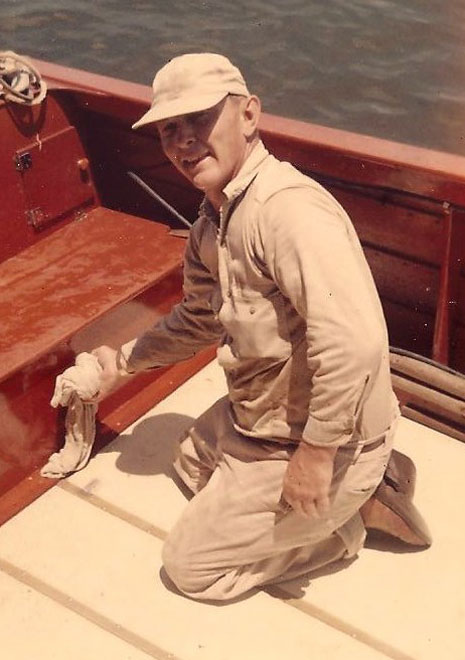

Berry and Bill in front of Bill’s house, circa 1960s. Photo courtesy of Cynthia Williams

One day an alligator got loose under the lunch room building and had to be lassoed, dragged out, and turned loose in the Caloosahatchee. It was a pleasure going to school in Florida because we could go barefooted, and didn’t have to take books home and prepare lessons. It seemed funny not having a book satchel slung over our shoulders, but we were all in favor of it.

One of the most interesting things we did in Fort Myers was sell the Evening Press on the streets every afternoon after school. We made one or two cents a paper and never sold over twenty or thirty. As soon as the papers came off the press and were counted out to us, I would hightail it around the corner to a large office with five or six men working. I’d give them the full sales pitch, telling them how superior the Evening Press was to the Tropical News. Usually one of them would buy a paper. Several months later, I found out that I had been hawking papers to the editors of the Evening Press.”

Elva’s brother found her a better job in Sarasota and in January of 1926, they moved. They were living there in a frame house on Adelia Avenue when the killer hurricane of 1926 struck. Storm-tracking technology as we know it did not yet exist, so on September 18, while this category 4 hurricane swept over Miami and churned on toward the west coast, the twins were enjoying ‘Son of the Sheik’ at the movies. When they stepped out of the movie theater, the wind almost knocked them down. They started to run.

In less than an hour the hurricane struck. The wind raged with a low moaning sound. We looked out the window and saw loose timber and sheets of tin flying by. Miss Elva screamed for us to get away from the window. The safest place she could think of for us was under the bed, so under the bed Davis, Bill and I went. As we lay there, we could hear the timbers creak in the house. In one terrific gust of wind, the upper part of the house almost parted from the lower half. We could see the timbers rise, then settle back again. We were scared, and made no attempt to hide it.

For almost two hours the wind and rain howled, then seemed to die away. When we were certain it had gone, we stepped out onto the front porch. The screen door handle was smashed flat against the wood. The little frame house next door was gone. We were in the eye of the storm. In about 20 minutes the wind returned, and for almost an hour more the hurricane raged.

When we thought it safe to go outside, we went out to see the damage. All electricity was off, the telephone lines were down, and hundreds of trees were uprooted. Thousands of guavas had been blown from the trees. Within the next few days, we found that whole sections of town had been flooded. Many families were having to get groceries from the top shelves of stores by rowboat. Broken glass was everywhere. The Associated Press reported that the sustained velocity of the winds had been 96 miles per hour, with gusts up to 120 miles per hour; that hundreds of people had been drowned at Lake Okeechobee when the lake overflowed. They were still trying to find and dispose of the dead. They were having to burn piles of bodies because they couldn’t bury them in the water-soaked ground.

The Florida bubble had burst, and almost drowned the state. Optimistic businessmen predicted that it would pass and Florida would boom again. Mother didn’t doubt that Florida would rise again, but she determined that would do it without her and her three children. She wrote her father and told him that we were coming home.”

During the post-WWII building boom of the 1950s, my father returned to Fort Myers with his wife and 4 children, bought the “beautiful, two-story white frame house” opposite the Elks Club on First Street, rented an office on the second floor of the Earnhardt Building overlooking the Arcade Theater and began wheeling and dealing in real estate. Bill followed with his family, and their kids went to Saturday morning westerns at the Arcade Theater. The price of admission had gone from 15 to 25 cents.

Florida had risen again.

Cynthia Williams is only one of the many narratives to come from Southwest Florida and the original link for her story can be found here in the News-Press! Cynthia Williams is currently a freelance writer for the Fort Myers News-Press, in which she features many other stories about family histories.

No comments yet.